Reading feels like treasure hunting, until challenging words blur the path. For children aged 3–8, reading should be magical, a pathway to imagination and adventure. But when they stumble over too many unfamiliar words, that magic fades, frustration builds, confidence shrinks, and reading becomes more of a stressful chore.

Research shows that when more than 5% of words in a text are unknown, early readers struggle to make sense of the story¹. The result? Cognitive overload, broken narratives, and lost enthusiasm for books²

Vocabulary shapes how children experience the world, from the stories they laugh at, to the opportunities they can access. Here are two powerful reasons why it truly matters:

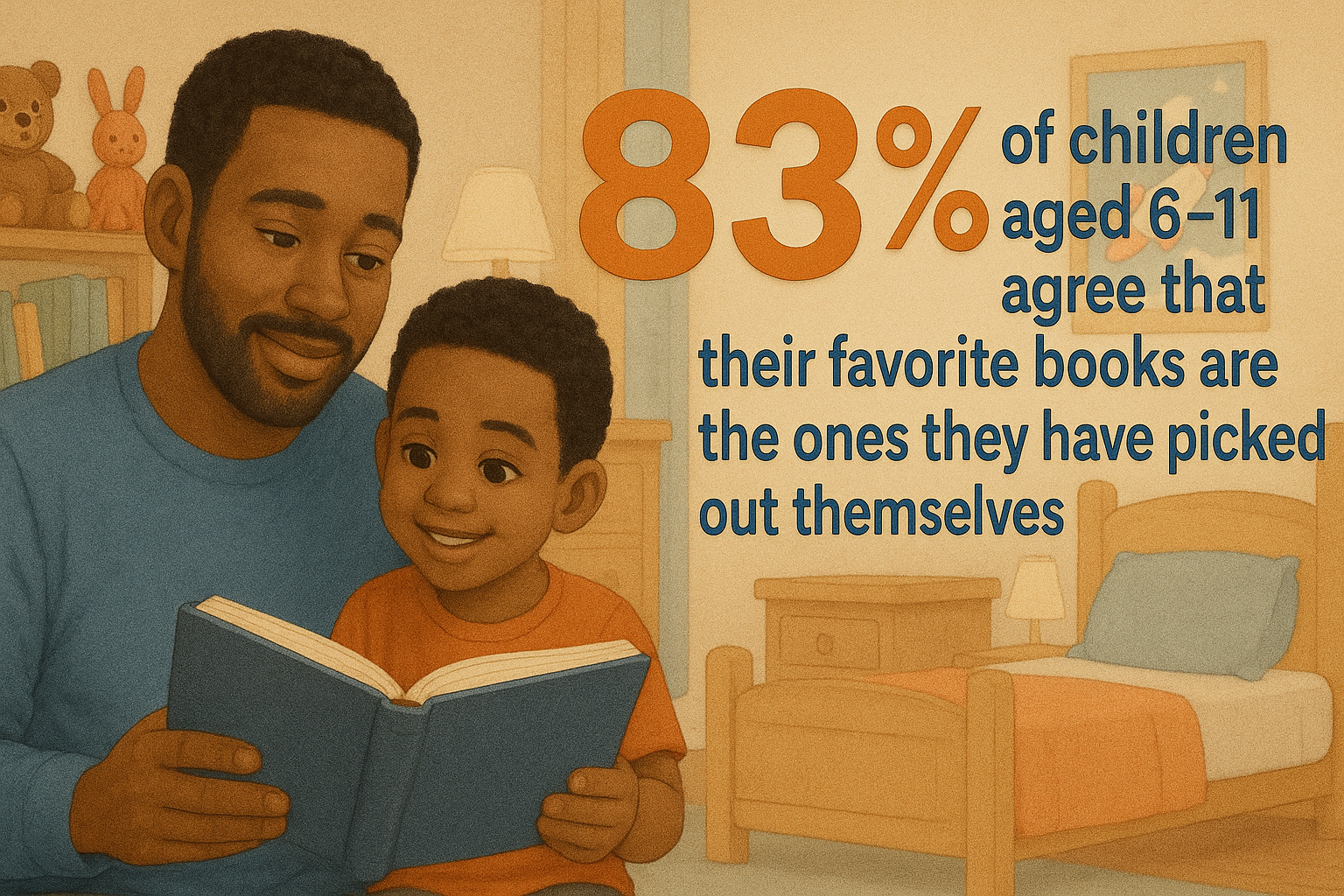

1. Strong vocabulary builds joy: According to the Kids & Family Reading Report™, 83% of kids ages 6–11 love books they choose themselves, and 89% prefer stories that make them laugh³.

When children know more of the words on the book, jokes make them giggle, stories come alive, and reading becomes a joy

2. Poor vocabulary creates unequal start: Research shows that by age three, children from high-income families hear 30 million more words than their peers from low-income households⁴.

Without early support, this gap only widens over time, a pattern researchers call the "Matthew Effect", where strong readers get stronger and struggling readers fall further behind⁵.

How then can we combat these vocabulary and reading gaps? Through, reading aloud, telling stories to kids, and letting kids choose books they love. Vocabulary blooms in environments rich with spoken words. Yet, while 77% of parents read to children weekly from ages 3–5, that number drops sharply after age 6³. Keeping the habit of reading to children is not just beneficial, it is transformational.

At Chronicle Creations, we understand the value of reading to kids and vocabulary. Our app Dreambook is designed for children aged 3–8 to co-create stories with parents, unlocking new ways to learn vocabulary, think critically, and fall in love with books.

Author: Grace Emmanuella Adaugo Oku, M.S. (Community Engagement Manager)

References

- Nation, K. (2001). Learning to read comprehension: The importance of vocabulary. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 71(2), 211–226.

- Perfetti, C. A., Landi, N., & Oakhill, J. (2005). The acquisition of reading comprehension skill. In M. J. Snowling & C. Hulme (Eds.), The science of reading: A handbook (pp. 227–247). Blackwell.

- Scholastic. (2019). Kids & Family Reading Report™: 7th Edition – Finding Their Story. Scholastic Inc. https://www.scholastic.com/readingreport

- Hart, B., & Risley, T. R. (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H. Brookes Publishing.

- Stanovich, K. E. (1986). Matthew effects in reading: Some consequences of individual differences in the acquisition of literacy. Reading Research Quarterly, 21(4), 360–407.

All Posts

All Posts