Not every child falls in love with reading through books alone. For many kids, their gateway into language, storytelling, and imagination starts with something unexpected: video games.

Especially for children between the ages of 5 and 10, narrative-driven games can play a surprisingly powerful role in supporting literacy development—when used intentionally and in moderation.

Here are five ways games like Pokémon, Zelda, or simple story apps can spark a lifelong love of reading:

1. Story games foster intrinsic motivation to read

When children feel ownership over a story—choosing their character’s name, making decisions in dialogue, or exploring a world—they're more likely to engage with the text. Games like Pokémon, Animal Crossing, or even story-driven apps require children to read instructions, clues, and character speech to succeed. This creates a natural reason to read, with comprehension tied directly to progress. Research shows that intrinsic motivation is a powerful predictor of reading volume and comprehension in young children¹.

2. Characters create emotional connections that deepen comprehension

In story games, players often spend hours with the same character—making decisions for them, seeing their reactions, and investing in their journey. This emotional connection enhances engagement and encourages deeper processing of the text. Children don’t just read about a hero; they become the hero. Studies have found that character attachment boosts narrative recall and vocabulary retention².

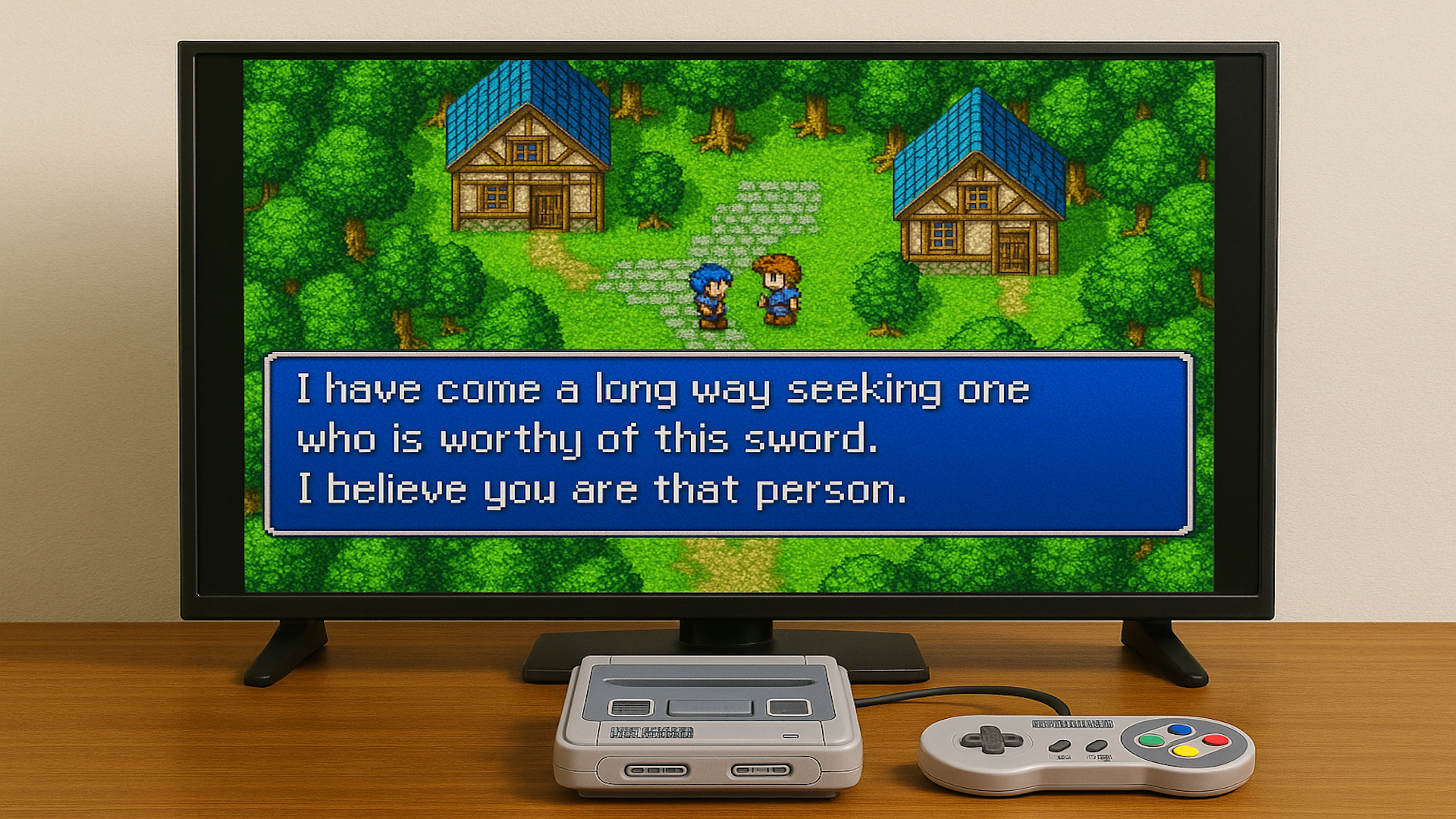

3. Interactive dialogue strengthens reading fluency

Unlike traditional books, games present text in short, conversational bursts—often supported by tone, animation, or audio. This mirrors how children naturally learn language: through back-and-forth interaction. Reading game dialogue mimics real-life conversation patterns, improving fluency, pacing, and context recognition³.

4. Visual storytelling supports decoding and comprehension

In video games, visuals and actions support the text: a flashing item reinforces a written clue, or a character’s facial expression provides context to the words. This multimodal input helps struggling readers decode unfamiliar words using environmental context. Research shows that pairing visual and textual information improves understanding, especially for early and ESL readers⁴.

5. Games can model narrative structure and world-building

Many RPGs introduce children to the building blocks of storytelling: quests, rising tension, climaxes, and resolution. They model how characters grow, how choices affect plot, and how settings shape emotion. Exposure to this structure helps children later construct their own stories and understand complex narratives in books. Vygotsky’s theory of the Zone of Proximal Development supports this: children learn best when scaffolded through meaningful, interactive experiences⁵.

Conclusion

We often separate “screen time” and “reading time”—but the truth is, children don’t. For them, stories are stories. When designed well, digital narratives can fuel the same love for characters, plots, and words that traditional books do. As educators, parents, and developers, we shouldn’t ask “books or games?” We should ask: “how can we use both to build a lifelong love of reading?”

References

- Guthrie, J. T., & Wigfield, A. (2000). Engagement and motivation in reading. Handbook of reading research, 3, 403–422.

- Mar, R. A., Oatley, K., Hirsh, J., dela Paz, J., & Peterson, J. B. (2006). Bookworms versus nerds: Exposure to fiction versus non-fiction, divergent associations with social ability, and the simulation of fictional social worlds. Journal of Research in Personality, 40(5), 694–712.

- Dowhower, S. L. (1987). Effects of repeated reading on second-grade transitional readers’ fluency and comprehension. Reading Research Quarterly, 22(4), 389–406.

- Mayer, R. E. (2002). Multimedia learning. Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 41, 85–139.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Harvard University Press.

All Posts

All Posts